Student athletes are not immune to mental health problems

College athletics’ plan to combat a spike in suicide among 15 to 24-year olds

January 30, 2019

Content warning: This article discusses topics of suicide and suicide prevention. If you are depressed or have suicidal thoughts please call the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-8255.

Suicide rates among college students and those aged 15 to 24 are at a 36-year high according to records kept by the Center for Disease Control, and student athletes are not immune to becoming part of the statistic.

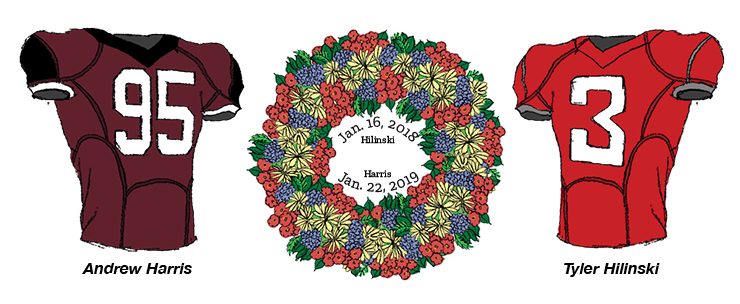

Andrew Harris was a senior defensive end for the University of Montana. On Jan. 22 he was found dead in his Missoula, Montana home of an apparent suicide. He was 22 years old.

Harris’ death came a year and six days after WSU sophomore quarterback Tyler Hilinski was found dead in his apartment with a self-inflicted gunshot wound. Hilinski was 21 years old.

At their lowest point in 1999, 3,901 teens and young adults took their own lives, climbing to 6,252 in 2017. Suicide is the second leading cause of death for people aged 15 to 24 according to the same CDC records.

When the EWU football team traveled to Pullman this past year, head coach Aaron Best laid flowers on the three yard line to commemorate Hilinski. Best said that he reached out to Montana head coach Bobby Hauck after Harris’ passing to let him know his (EWU) family was there with open arms if they need them.

“It makes you want to squeeze your kids a bit more,” Best said. “It makes you want to find ways to be creative and put your arms, eyes and heart around your guys. Part of coaching is building those relationships and knowing what your kids are needing and struggling with.”

This past week at the 2019 NCAA Convention, the Power Five conferences passed legislation that will mandate all schools in their conferences to, “make mental health services and resources available to its student-athletes through the department of athletics and/or the institution’s health services or counseling services department.”

Non-Power Five schools will not be mandated to comply with the new legislation, but will have the option to opt-in.

EWU Athletic Director Lynn Hickey said that this is something EWU is already doing for the most part, with help from the school’s counseling department.

“I think we have some good things in place,” Hickey said. “But I think we can be better. That’s an ongoing process. I don’t think you would ever get to a point where (you say), ‘yes we’re satisfied.’”

Hickey said that the athletic department has partnered with the Hilinski’s Hope—a nonprofit foundation created by Tyler’s parents to destigmatize mental illness. Hilinski’s Hope sponsored a workshop called Step UP! Bystander Intervention to speak to a number of universities’ athletic departments, including EWU last fall.

“The big thing is following up,” Hickey said. “Sometimes what happens is you’ll see something and everyone responds really well, and you jump to help the person, but you forget how much stewardship there has to be after the fact. It’s not just going to disappear.”

Hilinski’s Hope will also be sponsoring two more workshops at EWU in the spring with Step UP! part two and Behind Happy Faces—both workshops aim to educate on mental health. Hickey said she wants athletic trainers to be more informed on topics of mental health and be able to help detect warning signs.

Keely Hope is an associate professor in the psychology department, who teaches mental health counseling and has researched suicide prevention. She said that having professionals trained in identifying warning signals regularly involved with the team would go a long way.

“The stigma in our society is that you need to take care of yourself,” Hope said. “If you talk to somebody about not feeling 100 percent then you are (considered) less than. If the message you’ve received your whole life, either from your family, other teammates or coaches is that you just tuck in and get the job done, then you maybe wouldn’t seek help. There’s something to be said for this idea of normalizing it.”

Hope said that there are risk factors with the added stress of being a college student, and that she would guess student athletes have to balance that stress with the stress of competing on their team.

“We all need a little bit of help sometimes,” Hope said. “I really do think it’s getting better, but sometimes it’s hard to break through those messages we’re getting from every other place.”

Another risk factor associated with athletics is potential head trauma. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is a condition associated with repeated blows to the head. CTE can only be diagnosed posthumously, but can alter memory, personality, and increase aggression and depression.

A July 25, 2017 study published in the Journal of American Medical Association discovered that out of 202 brains of former football players, 87 percent had CTE. Out of 111 brains of former NFL players, 99 percent had CTE.

Hilinski’s parents revealed he was diagnosed with CTE six months after his death. His father, Mark said on NBC’s TODAY that the medical examiner told him that Hilinski had the brain of a 65-year-old.

EWU head athletic trainer Brian Norton said common perception is pointing toward CTE being diagnosed in someone who could have just one significant head injury.

“Research is starting to show it’s not just the NFL football player that’s played for 15 years,” Norton said. “It could be somebody who has been in an automobile accident and had a serious concussion. That damage to the brain just kind of persists on.”

Over the past few years football has evolved to focus on player safety. There are added protections to players with targeting calls that will eject a player from the game for leading with the crown of his helmet on a tackle, and there have been advancements in helmet technology.

Norton said that he worries more about high school and youth sports when it comes to concussions because of the difference in resources on the college and pro levels.

“A lot of times you may sign up to play Pop Warner and they have a room full of helmets,” Norton said. “They just find the best one that fits you and put it on you and say, ‘go’.”

Research on CTE continues, and athletic programs keep developing systems for dealing with mental health. While some blame football, neither Best, Hickey nor Norton blamed the sport as the main culprit for mental health problems in athletics.

“There’s not enough research done at this time,” Hickey said. “We had more concussions this year for volleyball than we did football. I do not believe we are doing anything that is harmful to our students.”•

![Simmons said the biggest reasons for her success this year were “God, hard work, and trusting [her] coach and what she has planned.”](https://theeasterner.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/image1-1-1200x800.jpg)

![Simmons said the biggest reasons for her success this year were “God, hard work, and trusting [her] coach and what she has planned.”](https://theeasterner.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/05/image1-1-600x400.jpg)